"Israeli Jets Have Bombed Syria...Are You Still There?"

Nine years after he fought his way out, battered and possessions destroyed, Trevor Ward returns to Syria to visit the 'must see' landmarks he had no idea existed.

This article first appeared on Sabotage Times in 2012

I once visited Aleppo in Syria, yet here I am staring at a magazine photograph of its most famous landmark and I don’t feel the slightest hint of familiarity.

“What, you don’t remember the citadel?” asks my wife. “But look at it, it’s amazing. And according to the article, it looks out over the whole city. How could you have not seen it?”

I don’t know. The photograph sends me on a mad, forensic scramble. My memories are incomplete but I still have the guidebook I took with me. I find the chapter on Aleppo and see that the 12th century citadel has a three-star – “not to be missed” – rating. And yet that is exactly what I contrived to do: miss it.

I find my photographs from the trip, but they end at Damascus. My camera was destroyed before I reached Aleppo. But there are other photographs: I borrowed a girl’s clunky, Instamatic camera to photograph my injuries. I find these in the bottom drawer of my bureau. It was summer 2001 and I’d just finished a contract as an adventure tour guide in Egypt and was travelling overland to Istanbul for my flight home. I was nine years younger, which you can just about make out through the bandages, cuts and bruises on my face.

I go back to the guidebook. I can’t remember the name of the hotel I stayed in, but I know that TE Lawrence and Agatha Christie had previously stayed there. According to the listings for Aleppo, it was the Baron Hotel. I locate it on the map in the book. It’s about a kilometre from the citadel. But it’s a couple of landmarks in the opposite direction from the hotel that catch my eye: a vast park and the railway station.

I remember spending a lot of time walking backwards and forwards through the park to the station to inquire about the weekly service to Istanbul. I can remember an ornate chandelier, a mural full of tanks and fighter planes, and being passed from one ticket window to another because no-one spoke English. Yet somehow I’d managed to make myself understood, because I eventually left Aleppo on a sleeper train. As we neared the Turkish border, my mobile phone had beeped to life with a text message from my girlfriend in the UK: Israeli jets have bombed Syria. Are you still there?

So it seems I’d spent most of my time in Aleppo trying to leave. Which makes me sad. From what I’m reading in my guidebook now, it sounds like a wonderful city I missed during my three days and nights walking backwards and forwards to the railway station.

I continue the excavations into my memory. Damascus is solid and complete but after that, things are a bit disjointed, like half-remembered dreams. A surgeon bending over me with ash dripping from the cigarette in his mouth. Mahran, the hotelier’s son who spoke perfect English, and his friend Ahmed who drove us across the desert in his 1950s Morris Oxford taxi. The girl who lent me her camera (though I can’t recall her name). The soldier who confiscated the film (which contained all the girl’s holiday photos. I had to buy a new film the next day to record my injuries).

After Damascus, I visited Palmyra, Krak and Hama and, like the citadel of Aleppo, probably missed their finest features.

“Would you like to go there?” I ask my wife.

“Syria? I’d love to. But are you sure, after what happened to you?”

I’m very sure. Almost a decade later, it’s time to return.

Our hotel in the Old City of Damascus, the Al Zaetona, is a lavishly converted merchant’s house in the Bab Touma quarter. Our four-poster bed is draped in finest Damascene lace and breakfast is served in a courtyard at the side of an ornate fountain. A few blocks away, an Arabic street sign has been usurped by a new nameplate declaring in English: “Handicrafts Lane”. Damascus has been well and truly boutique-ified since my last visit.

In the heart of the souk, where 500-year-old mosques and bathhouses jostle for space with spice and confectionary stalls beneath high vaulted ceilings, we meet Tariq who can do business in Arabic, French, German, English or Spanish. We settle on Spanish. At his prompting – and at my reluctance – the conversation quickly turns to religion. Were we Christian? If so, had we been to Maalula yet? I’ve never heard of it. It’s beautiful, says Tariq. It’s almost as if he senses my unease at “Handicrafts Lane”. Then he adds: “Y la gente hablan el idioma de Jesus Cristo todavia”. That clinches it. The following morning we take a minibus 50 kilometres north to the village where they still speak Aramaic, the language of Christ.

Three female American students are on the same minibus. All the way there they yap incessantly about mutual acquaintances, TV shows, holidays without once looking out the windows. When we arrive at Maalula, they barely acknowledge their surroundings as they continue their weightless chit-chat. The sights and sensations around them cannot permeate their bubblewrap of indifference. My wife and I are the only other non-Arabs on the minibus. By pointing at his watch, the driver tells us there are buses back to Damascus every hour.

The start of the footpath to the Greek Catholic monastery of St. Sergius is at the side of a gift shop selling cassette tapes of the Lord’s Prayer recited in Aramaic. A gradually ascending path leads us to the top of a narrow gorge, and from there we follow the trail of tourist buses to the door of the monastery. Pilgrims from all over the world come to visit what is reputedly the oldest Christian chapel on earth. After one coach party has dispersed, I ask one of the young female guides if she can say something in Aramaic. She blushes until her companion spurs her on. In a hesitant whisper that quickly grows louder with confidence, she gives a flawless recital of the Lord’s Prayer, her words bouncing off the stone walls before melting away in the candle-lit emptiness.

“As we neared the Turkish border, my mobile phone beeped to life with a text from my girlfriend: Israeli jets have bombed Syria. Are you still there?”

Before leaving, we ask the guide if she knows the way to the big statue of Christ which we’d seen dominating the hillside when we’d got off the bus. After a moment’s thought, she leads us out of the crypt, into the modern cafeteria, behind the counter and out through the kitchen door where we find ourselves at the top of a steep slope which plunges several hundred feet to the town below. She points to our left and there’s the statue. No path, no health and safety regulations, just a precarious scramble along the top of the embankment with only a chicken wire fence to hold on to. We decide to buy a postcard instead.

By co-incidence, we end up on the same bus back to Damascus as the Americans. They are still rabbiting on about a world that seems very far away.

The next day, we take a taxi to the bus station. We’re leaving Damascus for the desert town of Palmyra. “You’re not nervous?” asks my wife. I am but try to hide it.

A couple of hours out of Damascus, I begin scanning the desert, looking for a clue, a sign, any indication of what had happened here nine years ago, but it all looks the same in every direction.

More…

That Time I Called Former American Apparel Boss Dov Charney A C*nt The Night Ukrainian Militants Stormed My House Party

As we arrive in Palmyra, a sandstorm blows up, obscuring the view of the Roman ruins for which the town is famous. “Mafeesh”, says the receptionist at our hotel, “five minutes, it will pass.” The foyer is full of earnest-looking backpackers, exactly the sort of insipid tourists I used to ferry between the sights of Egypt, the sort of people who would complain about the condition of the donkeys we would ride to the Valley of the Kings but think nothing of stepping over limbless beggars on the streets of Cairo. A sign on the hotel noticeboard announces this group will be meeting at six to view the sunset from the Arab citadel overlooking the ruins. My wife and I will have to find a different vantage point.

I’d booked the Hotel Ishtar because I was convinced it was the hotel where Mahran had worked nine years earlier. Its description – cheap and cheerful – and location on the map – on the edge of town close to the ruins – seemed to match my own recollections. But the Ishtar obviously isn’t it, and the street we are on isn’t familiar either. It’s too busy, too happy. The place had seemed like a ghost town nine years ago. Or maybe that was because it had just heard the news that dozens of people had been killed a few miles down the road.

It’s only on the way to the ruins after the sandstorm has abated that I spot a crudely painted sign pointing down an anonymous side street: New Afqa Hotel. Inside is the same, featureless lobby where Mahran had struggled to find me a chair to sit upon as his father made us tea. This is where the three – Irish? - girls had recoiled in shock at their first sight of my bloated face before sitting down to hear my tale. It was then, barely 20 minutes after leaving the hospital, that I’d announced my plan to return to the scene of the accident and take photographs. One of the girls agreed to lend me her camera and Mahran would arrange for his friend Ahmed to drive us in his taxi.

But Mahran isn’t here now. Did he even still live here? The man behind the desk assures us he does and, by pointing at the clock on the wall, indicates he’ll be here this evening, inshallah.

Nine years ago, I’d wandered down the main avenue of Palmyra’s ruins in a daze. So much had happened during the preceding 24 hours that the treasures laid out before me couldn’t hope to compete.

I’d returned to the scene of the accident with Mahran and Ahmed, but a simple matter of taking some photographs had been complicated by the presence of dozens of armed soldiers who had cordoned off the wreckage. The commanding officer had recited al-hamdoulilah at the sight of my face, but was unsympathetic to my request to take photographs. He explained to Mahran that the bus had been full of army conscripts and the accident was now the subject of a military investigation. I had tried to sneak off some shots anyway, but the sound of the Instamatic’s manual wind-on mechanism gave me away. With Ahmed watching helplessly from his taxi, Mahran and I had been arrested, put into an army jeep and driven several miles down the road to a huge mining camp.

Now I am seeing the ruins properly for the first time. My wife and I are the only souls picking our way through the monumental columns, delicate arches and mysterious burial towers that litter the desert for miles around. The sensations I feel – warmth, happiness, wonder – are as inextricably linked to my personal history with this place as to the purity of the desolation around us. No visitor centre, ticket office or other concession to modern tourism here. No persistent hawkers, no stubborn guides, not a single obtrusive notice. A Bedouin riding a camel glides by. Eventually a necklace-seller on a moped does charm us out of 50 Syrian pounds.

By the time we reach the crest of a small hill overlooking the Camp of Diocletian, the colours of the desert and stones are deepening to crimson and ochre. We watch in silent solitude as the shadows lengthen across the sand. Behind us on the hill of the citadel, the sun glints off dozens of tourist coaches.

Mahran has put on a few pounds, but he says the same about me. Over sweet tea in the hotel lobby – again served by his dad – we reminisce about that day nine years ago when I, literally, stumbled into his life.

He’d heard there was a foreigner at the hospital and had turned up looking for business, unaware of the scale of the emergency unfolding there. He’d brought me back to his hotel, though I eventually had to disappoint him and tell him I had a reservation elsewhere.

Following our arrest at the scene of the crash, his cheerful demeanour had disappeared: “I was frightened, of course. I was about to start my military service that year, and here I was being arrested in the company of a foreigner. Syrians were not allowed to have contact with foreigners. It was only a few months before 9/11, remember.”

I couldn’t recall what had happened following our arrival at the mining camp, but Mahran could: “They took us to see the mine owner, who was the army general for that area. He wanted to know if you were a spy, and you refused to drink the tea he brought in for us. After he took the film from your camera, you threw a 20 pound note at him, saying ‘Thank you for the tea.’ My God, I thought we were going to be shot!” Instead, we were driven back to Palmyra and Mahran learned the general had already been in contact with his father to verify his story.

“I wrote to the Syrian Embassy when I got home,” I tell Mahran. “I wanted to see if I could send some money to the families of the people who died. But they said they had no knowledge of any accident.”

“Of course,” says Mahran. “Syria has to protect its image. Your tourist dollars are more important to us than the truth, my friend.”

Mahran eventually served two and a half years in the army, including a stint on the Golan Heights. Now he’s working for a gas exploration company during the day, doing shifts at the hotel in the evening and studying for a business degree until the early hours.

As we shake hands and promise to keep in touch, he tells me that he had a terrible accident of his own a few years ago: “It happened in here,” he says, slapping his chest. “She is the daughter of a pharmacist, and she lives here in Palmyra. But her parents didn’t think a hotelier’s son was good enough for their daughter. They stopped me from seeing her. But I will show them.” By getting your degree? “Either that or by killing them,” he smiles back.

“I’d wandered down the main avenue of Palmyra’s ruins in a daze. So much had happened during the preceding 24 hours that the treasures laid out before me couldn’t hope to compete.”

THE next day, we catch a minibus to the transport hub of Homs. On the way, the driver asks us our ultimate destination, and we tell him Qalaat al-Hosn, the Arabic name for the crusader fortress of Krak de Chevaliers. Rubbing his thumb and fingers together, he asks how much we’d pay if he took us the whole way after he’d dropped his other passengers off in Homs. We eventually settle on the equivalent of about £10, and arrive at the Pepars Hotel in time to see the sun setting on the castle directly across the valley from our balcony.

We have chicken and chips for dinner at the terrace snack bar opposite the entrance to the castle. The owner is so delighted with our presence – most tourists do Krak as a day-trip rather than an overnighter – he fills up his personal hookah pipe with apple tobacco and leaves it with us as the evening call to prayer floats up from the valley below.

In Hama, we’re enjoying a mezze of kibbeh(minced lamb deep fried in bulgur wheat), fattoush(parsley and tomato salad) and muhammara(puree of red pepper, tomato and spices) in the riverside garden restaurant of the Apamee Cham hotel, watching small boys jumping from the lazily churning paddles of one of the town’s famous water wheels, when I realise something is missing. Where I remembered vintage, bubble-shaped Mercedes taxis, the streets are now clogged with modern Japanese cars. I feel strangely sad. Either they’d never really existed on the scale my memory would have me believe – after all, I don’t have any photographs to offer as proof – or they are yet another unique detail of Syrian life forever erased by modernity.

In Aleppo I am finally walking the streets which have existed for so long in my mind as little more than shadowy, half-developed images. The Baron Hotel is instantly familiar and reassuring, the deep leather armchairs of its bar still occupied by groups of rubbernecking interlopers trying to make their cans of Egyptian Stella last all night long.

More…

Smoking Kif In 70s Morocco Echoes Of War: An Afghan Tourist Diary

Nine years ago, I only ever turned right out of the hotel. This time, my wife and I turn left, and soon we are sucked into the maze of sweet-smelling tunnels that signal the outer edges of the city’s sprawling covered souk. Before we slip completely into the half-light, a vendor digs deep into a basket and hands my wife a handful of pink rose petals. It’s a simple gesture, a sales ploy really, but it makes us smile. Previously, I’d wanted to leave Aleppo as quickly as possible. Now I’m already feeling as if I could stay here forever.

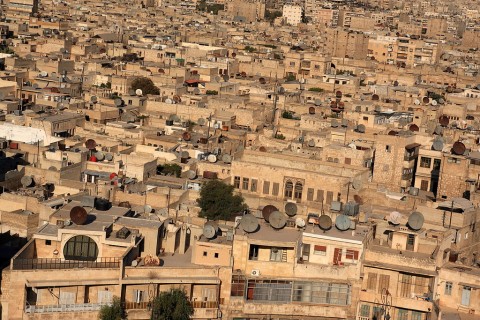

It’s inevitable that we will emerge, a couple of hours later, at the opposite end of the souk and find ourselves at the foot of the citadel, the three-star attraction I somehow missed all those years ago. We cross the monumental stone causeway and take the winding stairway up to its well-preserved ramparts. From the top, we look down upon a forest of satellite dishes and minarets. We are also able to preview various rooftop terrace restaurants we will eat at during the next few days.

Aleppo seems to stretch to the horizon. One by one, like old gramophone players being cranked up to speed, the muezzin begin the afternoon call to prayer. There’s hardly a cloud in the sky. The sweet aroma of apple tobacco wafts from below. The woman who was my girlfriend nine years ago is wrapped tightly in my arms.

Everything seems wonderfully familiar.

From the BBC World Service News website, Wednesday 27 June 2001, 14:31 GMT:

Bus Crash in Syria Kills 27

A truck has collided with a bus north-east of the Syrian capital, Damascus, killing 27 people and injuring 15.

The accident happened on the road to Palmyra when the truck tried to overtake another vehicle and collided with the bus coming from the opposite direction.

If you like it, Pass it on

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

bloody hell, what a story. Would make a great screenplay

Brilliant article, so evocative and moving. And fantastic pictures. Congratulations and thank you for a great piece of writing.

great article ned more real life dramas like this and stunning well written a forgotten art these days

An outstanding piece of writing that avoids all the tiresome cliches typically found in articles about Syria. That last paragraph made the hairs on my neck stand on end. I remember standing on the balcony at the Hotel Riad in Hama at sunset, listening to the muzzein start up one after the other. With so many mosques in such close proximity it should have been a din, but instead it was the most perfect harmony with voices rising and falling like waves. An extraordinary feeling.

I agree with the above reviews..beautifully wrote and left nothing to the imagination...I felt as if I was there with you...too true this must be made into a screenplay at the very least!!!!!

Hi Trevor, So glad to have found your reportage! Back in 2004 I stayed at the New Afqa Hotel in Palmyra and was fortunate to spend a few days with Mahran and Ahmed. Mahran treated me as family and made sure I had the best time possible in Palmyra. We had som great conversations too - he's a great guy! Unfortunately I did not get any address or other way of keeping in touch with him, something I regret to this day. I often think of him, especially now... Are you still in touch with him? I really would like to get in touch with him, or at least know how he's doing. Any information you have would mean a lot to me. Many thanks, Pauline

RELATED

RELATED

SABOTAGE

SABOTAGE