The 60s ended when John F. Kennedy was shot by Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas, 1963.

The 60s ended when Sharon Tate and some friends were killed by members of Charles Manson’s ‘family’ in 1969.

The 60s ended when Meredith Hunter was killed by a Hells Angel during The Rolling Stones’ free concert at Altamont, also 1969.

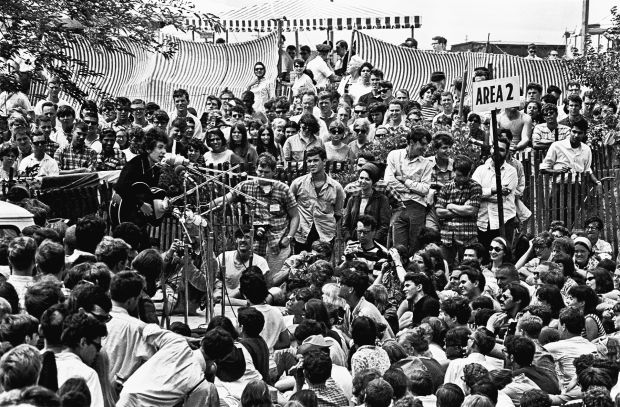

The 60s ended when Bob Dylan took the stage at the Newport Folk Festival backed by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, plugged in, and launched into a loud, Chicago-rock version of Maggie’s Farm, in 1965. The 60s that, up until that point, belonged to Dylan, belonged to Blowin’ In The Wind, belonged to this idea of him as an important voice, a figurehead for a scene, a scene that crystallised itself in Newport. A scene that fractured when he walked on stage holding a Fender Strat, and not a Martin 00-17.

The question here, and one that Elijah Wald attempts to unpack in his brilliant new book ‘Dylan Goes Electric!’, is how does a man become a myth? How did Dylan go from being a nerdy, excitable, eager kid from Hibbing, Minnesotta, to being the coolest man in the world?

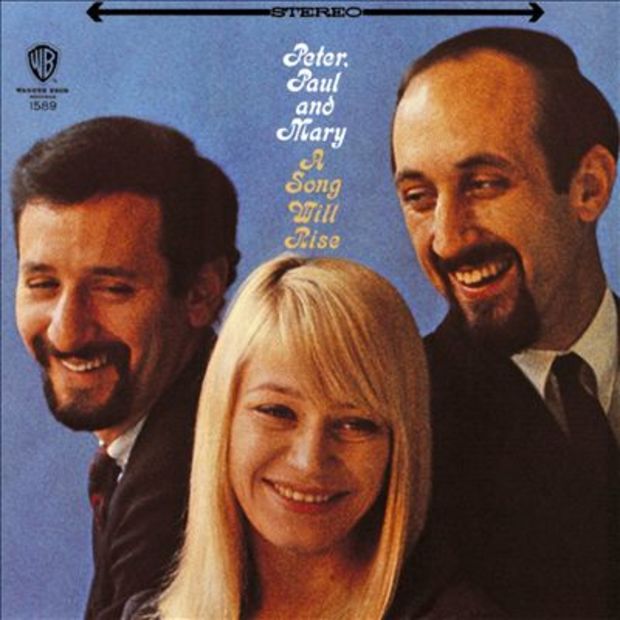

That’s the point, too. Dylan may have been huge, but in comparison to some contemporaries, he wasn’t shifting huge units himself. Blowin’ In The Wind, Mr Tambourine Man, It’s All Over Now (Baby Blue), All I Really Wanna Do…all those iconic, huge Dylan hits, weren’t Dylan hits at all; they were Peter Paul & Mary hits, The Byrds hits, Joan Baez hits. Dylan was covered by hundreds of acts who all sold more records than his did, but Dylan was still the one people clamoured for.

What Wald does a great job of establishing in the book is just how different the music scene of the early 60s was from what we think “60s music” is. You’ve got to remember that though the 60s became a period of youth in revolt, free love, protests and drug experimentation, America was in a very different place coming into it, and the generation gap wasn’t nearly as chiasmic as it was about to become. This was reflected in the music too – even the protest singers, the ones who had a young audience and were deemed ‘controversial’, when you look back on them now, were square. This is the aforementioned Peter, Paul & Mary (left), who were huge

Receding hairlines and accountant’s suits. Goatees, for fuck sake. Mary was brought in specifically to give them more appeal, which is totally understandable. Another example? Take a look at The Kingston Trio below.

Would you look at these nerds? These guys had fourteen top 10 records. In 1961, The Schnectady Gazette described them as “the most envied, the most imitated, and the most successful singing group, folk or otherwise, in all show business”. It was music for twee, earnest, socially conscious college kids, who wore sweaters and used pom-ade and hadn’t dared to pick up The Kinsey Reports yet.

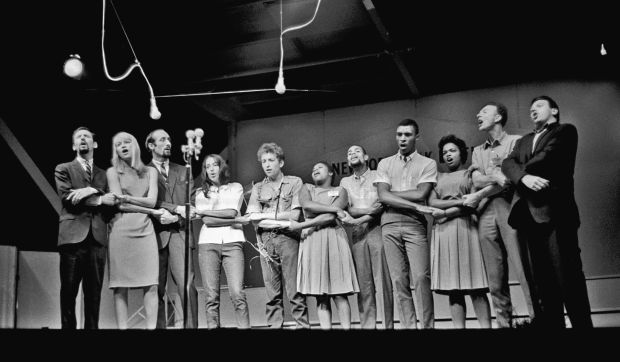

Both these bands headlined the Newport Folk Festival, set up as an offshoot to the Newport Jazz Festival right at the start of the 60s, by folk purist Pete Seeger, the other key figure in Wald’s book. Seeger and Dylan represented the old and the new versions of ‘folk’ – Seeger a total traditionalist who believed in folk music as preservation, almost as ethnographic study. A staunchly political giant of a man who led sing-alongs of We Shall Overcome and This Land Is Your Land, and was banned from many mainstream TV and Radio outfits for his communist sympathies, but whose songs sounded still choral, churchy and, to be honest, gutless. He should be credited for giving a huge platform – and Newport was huge – to old blues singers like Son House, Mississippi John Hurt, and Skip James, but there was no shred of the passion or timbre or meaning of the blues in Seeger’s music. In his mind, it wasn’t his experience being sung, so he didn’t sing it.

Dylan, on the other hand, was a kid schooled on James Dean and Marlon Brando, who liked to bury himself in different musical styles and spit them back out in his nasal drawl. He was a movie star, singing songs that that movie stars hadn’t yet sung up until that point. He was a folk singer, on that first album at least, recording traditional tunes (only two on his debut were written by him, and they’re both aping Woody Guthrie), but he looked different. Acted different. He was funny, youthful, engaging, exhuberant, a bit manic, a bit wild, and the generation of folk singers above him saw in him their traditions being taken forward into a new decade full of hope and promise.

When Seeger looked at Dylan, he saw all the traditions that he loved being taken forward and given to a new generation. Dylan’s manager however, Albert Grossman, saw a big dollar sign with a guitar, and this was the origin of the tension that led to Dylan plugging in. The problem wasn’t with electric music as a concept – people played electric sets at Newport in 1965, and in previous years too, no bother. The problem, and it had been becoming a problem throughout the 60s, was that the festival had turned into a bit of a market place, and Grossman was at the centre of a lot of it, which got the hackles up of Seeger, and fellow music preservationists like Alan Lomax. Grossman had already had a fight with Lomax, and by Wald’s estimation, put Dylan together with the Butterfield Blues Band…well, to wind him up, basically. Dylan had already made electric records by this point, so it wasn’t totally new, but the sheer volume at which he went out, the aggressive soloing from Butterfield, the lack of practice, the lack of care for his audience. There was the change.

The interesting thing, narratively speaking, is that a year after Newport – a year in which Dylan toured with his electric band (who would, in part, later go on to become The Band) and was met with hostility from mostly every crowd, including that famous “Judas!” moment – Dylan had a motorcycle crash, and disappeared. Dylan’s 60s ended four years before the decade did, but his influence was felt pretty much everywhere, musically speaking.

Because what Dylan had done, throughout the decade, culminating at Newport, was spun a groovy, suited, chaste rock and roll, into a charged, powerful, socially engaged rock, sewing the seeds of punk in the process. Popular music was now the weapon-of-choice for people who wanted to shout about the government, or Vietnam, or the sexual revolution, and that’s down to Dylan. Some of that audience from his folk days went with him, others stayed with Seeger.

What Wald’s book illustrates, perhaps better than any other, is how this change comes about – at first, by degrees, and then all of a sudden, no turning back. In characterizing Dylan as this eager, musically literate kid, he also goes some way to explaining the multiple changes throughout his career – from folk singer, to rock and roll star, to Christian evangelist, supergroup sideman, and most recently, Sinatra impersonator. Despite the hostilities he’s faced, Dylan has retained his appetite for music, which has kept him on stage for so long. Some people boo, but he knows he’ll always take some people with him, and pick up stragglers along the way.

Follow Harry on Twitter - CmonHarris

Dylan Goes Electric! Newport, Seeger, Dylan and the Night That Split the Sixties by Elijah Wald is published by Harper360, 13 August 2015, £16.99 Hardback. Get it here