Few people have made the transition from wunderkind to washout as quickly as Orson Welles. When the 24-year-old Orson looked over the set of Citizen Kane, he described it as “the biggest train set a boy ever had.” Six short years later, Welles’ career was so badly derailed, he was reduced to knocking out a bargain basement Macbeth.

There were countless reasons for Welles’ fall from grace – the arrogance of youth, the envy of others, the Hearst press’s reaction to Kane. However, as time slowly drifted by, it seemed increasingly likely that The Lady From Shanghai (1947) would remain Welles’ last American studio film. That was until Charlton Heston stuck his oar in.

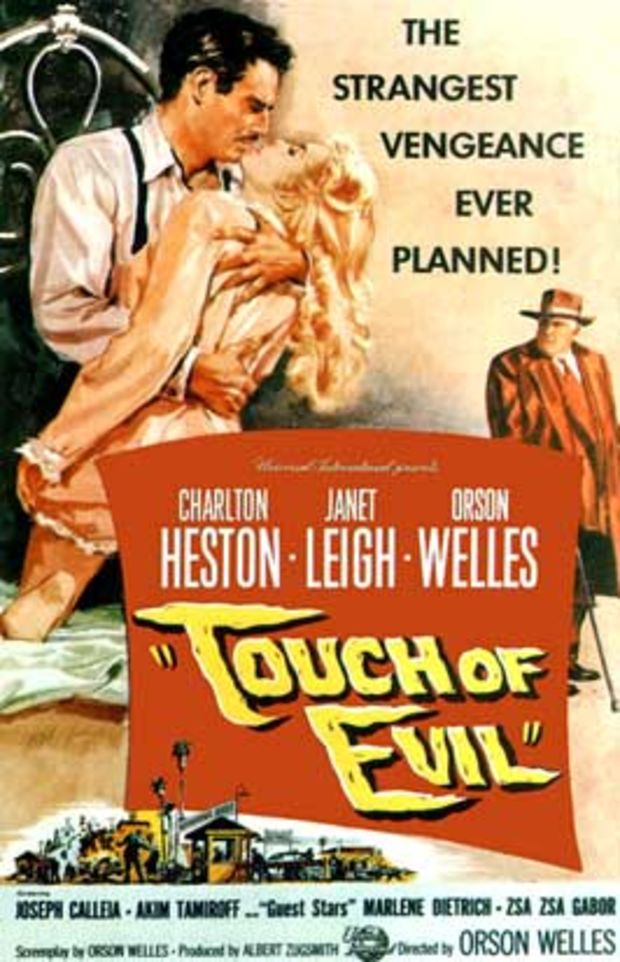

By 1957, there were few bigger actors on Planet Hollywood than Chuck Heston. A household name thanks to The Ten Commandments, Universal considered itself very lucky to sign him up for Badge Of Evil – a little noir number designed to prop up the financially unstable studio. On enquiring about his co-stars and director, Heston was told that, while a filmmaker hadn’t been assigned, he’d be sharing the screen with Janet Leigh and Orson Welles. “Well, how about having Orson direct it?” asked Heston. “You know, he’s made some pretty good movies.”

Keen to keep their star happy, Universal grudgingly allowed Welles to direct the rechristened Touch Of Evil. Being aware of Orson’s reputation for excess, the execs insisted he leave the script alone. Of course, Welles took no notice and penned a new screenplay within 72 hours. The director also insisted on taking the project off the backlot, choosing to make his movie at the LA beach resort of Venice. The shift in location combined with Orson’s demand for numerous night shoots led the producers to fear they might be losing control of their picture. Perhaps a visit to the Evil shoot would soothe their nerves…

“The first day,” says Heston, “it was a complex scene, 13 pages scheduled for three days. Lunch went by and uneasy groups of execs began to huddle in the shadows, increasingly convinced they were on the brink of disaster, because we hadn’t even turned a camera on. Finally at 4.30pm we turned. Just before 6pm, we got a print. Orson said, ‘Wrap. We’re two days ahead of schedule.’ Thirteen pages in one day – amazing!”

Superb artistry wasn’t the only thing Orson brought to Touch Of Evil. He also added value to the picture courtesy of cameos from close friends Zsa Zsa Gabor, Joseph Cotten and Marlene Dietrich. This came as a welcome surprise to the producers, as Welles recalls. “They’d be watching the rushes and they’d say, ‘That’s Dietrich! How did you get her?!’ After that, they went out of their way to compliment me for the rushes every night.”

With the producers seemingly content, Welles was free to bring his own flavor to Touch Of Evil. Commissioned as an unfussy money-making enterprise, the writer-director seized on the story of a Mexican-American detective (Heston. Yes, *Heston*) investigating a border country murder to the chagrin of a local cop (Welles) and transformed it into a noir so warped, it bordered on black comedy. Such a change was made possible by playing up taboo aspects of the story concerning drugs, sexual assault and prostitution. The vicious rape of Heston’s on-screen wife Janet Leigh was especially daring given that it was over-seen by a leather-bound lesbian (Mercedes McCambridge).

More...

Naturally, when the appalled producers came upon this material, they did all they could to ‘salvage’ their picture. This included firing Welles from the editing, reshooting certain sequences and then setting about Orson’s footage with garden shears.

To say Welles was upset with Universal’s meddling is like saying the Russians were a bit miffed about Stalingrad. Upon seeing the studio’s cut, the filmmaker dashed off a multi-page memo highlighting each unnecessary alteration. Eventually, this missive would enable editor Walter Murch to reconstruct Evil so that it resembled Welles’ intended version. At the time it was written, however, the memo was little more than an expression of utter frustration.

All of which said, it initially appeared that it would be Welles, rather than the execs, who had the last laugh. Premiering at the Brussels Worlds Fair, Touch Of Evil promptly scooped the Best Picture prize. In America, though, the movie wasn’t so much released as flushed. Stuck on the bottom half of a double-bill, it instantly disappeared from theatres. Disappointed, Orson Welles retreated to Europe where he tried to drum up money for an adaptation of Don Quixote. Charlton Heston, meanwhile, buggered off and made Ben-Hur.

Given the quality of the completed film – cuts or no cuts, Touch Of Evil is up there with Welles’ very best work - and the harsh treatment handed out to him by Hollywood, it’s tempting to see the great man as the scorned party in the Evil affair. But look at the matter again and you can understand the studio’s grievances. Having asked for a bog-standard thriller, it must have come as quite a shock to receive a pitch-black noir so soaked in sex, drugs and violence as to be almost unreleasable in the soporifically sedate 1950s.

More pertinently, Welles’ failure to go along with the studio’s wishes did irreparable damage to his career. While it’s unpleasant to think of a world without Touch Of Evil, had Orson played by the rules, he might have had the opportunity to make other, more personal pictures for Universal. Perhaps spoilt by the stipulation-free contract he signed with RKO to make Kane, Welles seems to have felt that any sort of compromise would tarnish his artistic integrity.

And well it might. But in playing his paymasters for fools, Welles ensured that he sullied both his directing and acting careers. For rather than being able to pursue roles that really interested him, Orson’s reliance on self-financing his films meant that he was forever having to take on terrible (albeit terrifically paid) parts in bloody awful movies such as Necromancy and Butterfly.

And while he might not have been the best at owning up to his mistakes, Orson Welles was fully aware of the compromise he’d forced upon himself. As he’d later explain, “I have wasted the greater part of my life looking for money and trying to make my work from this terribly expensive paint box. I’ve spent too much energy on things that have nothing to do with making a movie.”

Threadbare Films

Orson Welles’ guide to cinema on a shoestring

Othello – Completed using Welles’ Third Man money, this Palme d’Or winner was shot in two countries over three exhausting years.

The Trial – Kafka adaptation shot in Paris’ abandoned Gare D’Orsay railway station because Welles couldn’t afford to rent studio space.

The Immortal Story – Based on a Karen Blixen short story, this barely feature-length drama was completed with money from a French TV company.

The Deep – A shortage of funds caused Welles to can this sea-bound drama. The death of leading man Lawrence Harvey also didn’t help matters.

F For Fake – Orson’s excellent look at the world of forgery was fleshed-out by ‘borrowing’ footage from a BBC show on the same subject.

Touch of Evil is available to buy on Amazon now