What Maisie Knew star Julianne Moore handles a close-up as well as anyone in Hollywood – which provides a perfect excuse for charting the device’s impact upon the face of cinema.

“Alright, Mr DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up.” As lines of movie dialogue go, Gloria Swanson’s famous command is right up there with “I coulda been a contender” and “Forget it, Jake, it’s Chinatown.” But as far as the history of the close-up is concerned, it’s another of Norma Desmond’s comments in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard that hints at the importance of the cinematic breakthrough. “We didn’t need dialogue,” snaps the fading star when asked about working in the silent era. “We had faces!”

The first ever face to appear on film in close-up belonged to one Fred Ott who was photographed while sneezing by inventor Thomas Edison in 1894. At only seven seconds long, the catchily titled Edison Kinetoscopic Record Of A Sneeze could hardly be described as a feature film. But it wasn’t long before the early Hollywood studios were using the technique in their movies. Not that audiences knew what to make of the close-up. The very people who were frightened by such mundane images as a train pulling into a station were equally scared by the sight of a person shot from the shoulders up. As historian Rob Lewis explains, “Audiences didn’t know what to make of the fact a man was missing his legs, arms and torso. It sounds ridiculous today, but in the early 1900s, the close-up seemed like the very worst kind of technological witchcraft.”

If movie-goers were intimidated by the close-up, the studios and the early movie stars were quick to seize upon the device’s power. In Fame In The 20th Century, Australian writer Clive James claims that the introduction of the technique was one of the foundation stones of modern-day celebrity. Certainly the human face had never before seemed so big. And with the moving image adding an amazing air of intimacy to the portrait, cinemagoers found themselves in the odd position of being incredibly familiar with the face of a complete stranger.

Although he certainly wasn’t the first Hollywood director to use the close-up, DW Griffith was amongst the earliest filmmakers to exploit its potential. Watch Intolerance, The Birth Of A Nation or any of Griffith’s other epics and you’ll see him use the tactic time and again. Indeed, Griffith’s overuse of the technique - combined with the fact that he had his stars wear the most ludicrous make-up to exaggerate and emphasise their features - means that his groundbreaking pictures now seem rather ridiculous (not to mention, incredibly racist). It was the so-called ‘Father Of Film’, though, who saw how useful close-ups could be used in terms of introducing a character or establishing his or her importance. And as far as showing emotion was concerned, Griffith, like the thousands of directors who followed him, knew that nothing beat moving the camera in close on the human face.

More...

“The power of film is an actor’s face.” So confirms the Hungarian filmmaker Istvan Szabo who’s employed close-ups with considerable success in films such as Mephisto, Sunshine and Being Julia. But while he’s aware that it is an important cinematic technique, Szabo is also keen to point up one of the device’s great ironies. “In all my experience of filming actors in close-up, the one’s who respond best are those with theatrical backgrounds,” he continues. “One would think that it is those who are schooled in camera technique who would know how to best use the camera. But since theatre schools an actor in being able to inhabit a character for hours at a time, it is stage trained performers - in my experience, people like Klaus Maria Brandauer, Ralph Fiennes, Jeremy Irons and Annette Bening - who can take the close-up and make it sing.”

From the wide-eyed acting of silent screen goddess Lillian Gish to the subtleties of the realist actors of the ’60s and ’70s, close-up technique has changed with the times. It also seems to vary from actor to actor, as the aforementioned Jeremy Irons explains. “What the camera requires is absolute emotional nakedness. When I worked with Meryl Streep on The French Lieutenant’s Woman, she said to me, ‘When the camera comes to you, you always turn away or hide from it. You mustn’t do that. You must be completely open to the camera. The camera is your lover and you must share everything with it.’ Now, being the archetypal Englishman, I thought this sounded rather vulgar and I still sometimes refrain from doing so. But Meryl Streep being Meryl Streep, she’s quite right, of course!”

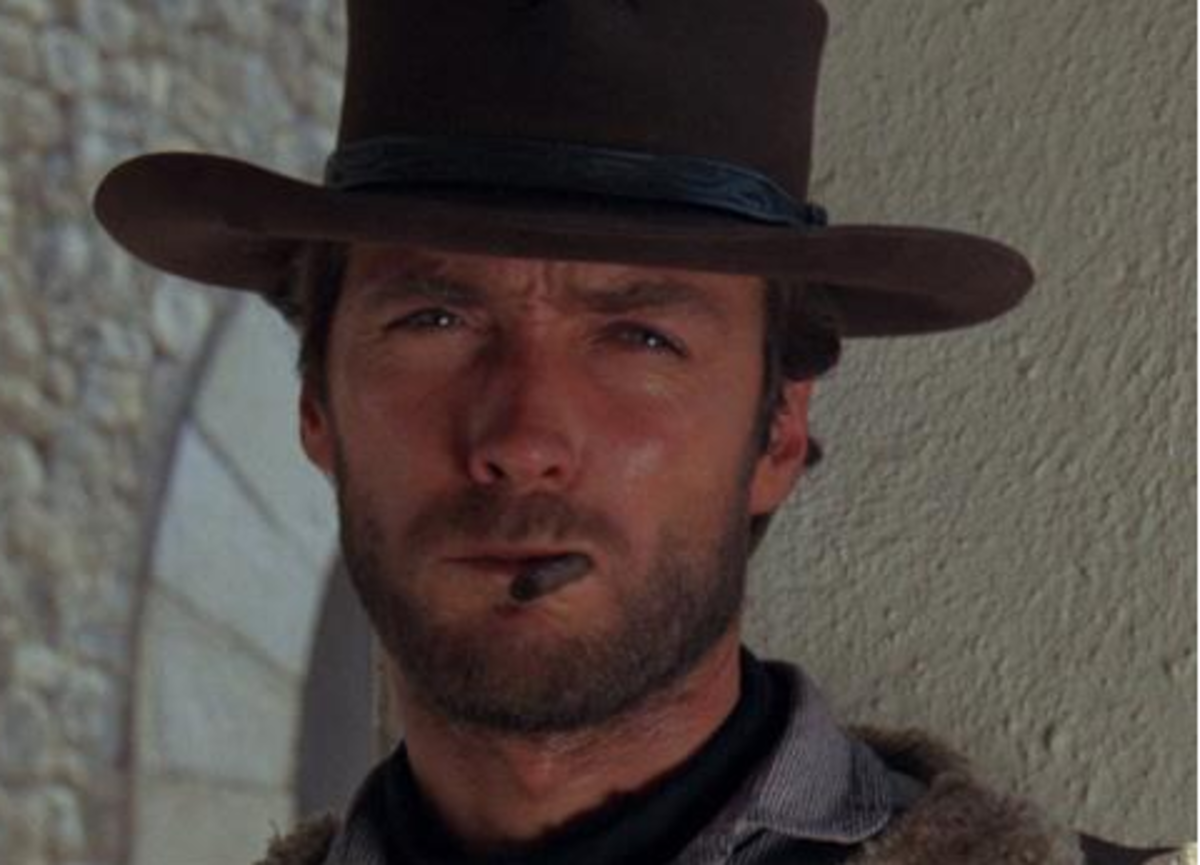

While it has long been a staple of cinema, the importance of the close-up has altered from decade to decade. In the 1960s, Italian director Sergio Leone made great use of the extreme close-up in his Dollars trilogy. More recently, directors such as Alex Cox have almost entirely done away with the device, preferring to shoot their pictures entirely in master shots. Even TV - where the power of the close-up is increased by proximity to the picture - has somewhat tired of the technique, with shows such as The West Wing preferring to use more subtle methods.

This reluctance to bring the camera to the actor is, of course, very bad news for the performer. “I was always told to save my best work for my close-ups,” the great Sir Michael Caine remembers. “Which was a big problem when I came to work with Woody Allen on Hannah And Her Sisters in the mid-’80s, because he doesn’t cutaway to close-ups at all - the only close-ups you get come organically out of the master. Naturally, I used to tease him about this, but he said I didn’t have anything to worry about. He’s a clever man, that Woody Allen.”

That Caine received his first Academy Award for his ‘close-up-free’ performance in Hannah illustrates that, while the close-up might have become an integral part of film, it’s not the key to every great performance. Still, without the device, film as we know it wouldn’t exist. And, likewise, our notion of celebrity might be quite different. After all, how else would we have come to pour over Harrison Ford’s pores as if they were craters on the Moon? Indeed, just as telescopes have allowed us to explore the firmament, so the close-up has brought us that much closer to the stars.

What Maisie Knew is available on DVD and Blu-ray from 10 February (Curzon Film World)