When acclaimed author Peter Biskind set about penning his Easy Riders, Raging Bulls follow-up Down And Dirty Pictures - a history of modern independent cinema - he was dead certain about who’d be the first person he’d call up. Sure, Harvey and Bob Weinstein and Quentin Tarantino were near the top of the list, but there was another man, arguably the greatest actor of his day, that Biskind wanted to track down first. Tattooed neo-Nazis, dual-personality psycho killers, scuzzy cardsharps, schizophrenic office workers - yep, it didn’t matter how low-down the picture, Edward James Norton Jr could get the character down pat. “But Peter,” the actor protested when Biskind’s call finally came, “don’t you realise that I’ve never made an independent movie?”

Biskind’s faux-pas is easy to appreciate. Over the course of the mid-to-late ’90s, the relationship between the Hollywood studios and their indie counterparts had grown so close as to seem almost incestuous. Clearly shaken by Billy Crystal’s crack about the 1997 Oscars nominations resembling “Sundance-By-The-Sea”, the old movie houses in part saw off the opposition by creating their own edgy film outfits such as Fox Searchlight and Dimension, the latter the sister to the now-mainstream Miramax. If said attempt to recreate indie cool sounds rather sinister, it’s done wonders for the studios with regards to retaining talent. In the past when a star got uppity, they’d be given something to direct. Now when someone talks about wanting to get back to their roots or trying something new, they can do so without even leaving town.

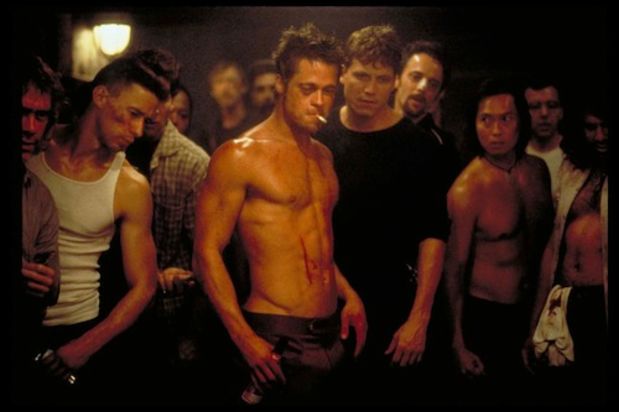

When Tom Hanks was promoting The Ladykillers (itself a product of Disney off-shoot Touchstone), he said that his first love was the stage - “It doesn’t get much better than performing Shakespeare before a live audience,” said the star of Dragnet and The Man With One Red Shoe. The Oscar-winner’s not alone when it comes to considering theatre as the ultimate acting challenge. But with Broadway a long way from LA - and the pay so damn terrible - movie stars have to content themselves with their brain-dead sequels and massive salaries. Or at least this was the case until the mini-majors started up. Now when a performer wants to do something gritty or personal, you just hook them up with the coolest new kid on the block. Cameron Diaz wants to do dowdy? Pair her up with Spike Jonze and a bad wig for Being John Malkovich. George Clooney wants a crack at being low key? Let him loose on Anton Corbijn’s The American? Tom Cruise wants to be a potty-mouthed bad-guy? Introduce him to Paul Thomas Anderson. Brad Pitt and Jared Leto are sick of playing pretty boys? Let them knock seven bells out of one another in David Fincher’s Fight Club. Yes, should a star now hunger for something original or alternative, their appetite can be straightforwardly sated.

Not that this move into a new arena has been completely pain-free. When Fox exec Bill Mechanic agreed that Fincher’s Fight Club adaptation should made for millions rather than done of the cheap, it was he who was asked to leave the building when the movie died at the box-office. Of course, Fight Club would go on to become the biggest DVD of its day, but by then Mechanic was reinventing himself as a producer-for-hire.

More...

The desire to dip a toe into alternative cinema has also resulted in studios finding themselves with difficult to market movies. Fox, for example, had so little idea of what to do with Donnie Darko, they cut a range of trailers that suggested the film was everything from a sci-fi horror movie to a John Hughes-esque high school romp. That Richard Kelly’s breathtaking debut grazed these and many other genres is by the by - confronted with something new and challenging, the studio fumbled the ball, leaving Donnie Darko to be rescued by word of mouth.

The march of the mini-majors has led to the mangling of all manner of movies. Shot as a pilot for a TV series, David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive was unceremoniously dumped by its American financiers and only made it to the movie theatres thanks to an $8 million investment from France’s STUDIOCANAL. But for every film the system has chewed up, Hollywood’s deep pockets have allowed some remarkable indie dreams to be realised. Regardless to what you made of the finished picture, it’s hard to believe that Richard Linklater’s Waking Life - a 100-minute long , narrative-free animated movie about philosophy and the nature of dreams - would have got made had Fox Searchlight been unwilling to sign the cheques. Likewise, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia - on the face of it, a three-hour film about tenuously-connected nobodies - might not have come into bloom without the help of the leftfield-friendly New Line. And, on both occasions, the studios in question were rewarded for their daring - Waking Life made an unlikely $3 million at the US box-office alone while Magnolia turned a $10 million+ profit on its $37 million investment *and* secured a hat-trick of Academy Award nominations.

And as long as the occasional oddball offering continues to do well financially, the Hollywoodisation of American cinema seems set to continue. However, should the edgier productions start to under-perform, it won’t be long before the majors bring down the portcullis and start spending their cash on more familiar fare. And while the underground and the overground might now share some common ground, the fact remains that truly alternative movies such as Sundance 2014 sensation Whiplash ought to be more dependant on the helping hand of Robert Redford’s Utah-based film festival than the throttling affect of the mainstream industry.